Insights from Yale's Well-Being Course

Do you remember the periodic table from when you memorized it as a kid? Has it served you well as an adult? How many times have you used the Pythagorean theorem to solve a significant problem? Sadly, our school curriculums are built mainly on subjects that are useless for most people once they graduate from the classroom.

Even more damning, critical lessons are largely absent. The United States is in the midst of a health crisis where over 40% of the population is obese (according to the CDC). Yet nutrition and exercise aren’t taught in a meaningful way. Our children learn about various rock types (remember igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic) but learn little to nothing about wellness. Many kids can recite historical dates and list the Presidents in order but don’t know the first thing about developing good habits, compound interest, or healthy relationships.

Fortunately, technology provides a gateway to information. I read about Yale’s Well-Being course, a popular choice among first-year students, and decided to check it on Coursera. Taught by Laurie Santos, the class helps students be happier and more productive by revealing misconceptions about happiness and the biases that hinder it. Over 3.5 million people have enrolled, a testament to the need and longing for this kind of education.

In a series of posts, I’ll share my favorite lessons from the course, along with thoughts and a few criticisms.

Knowing isn’t Half the Battle.

I remember sitting in Ninja Turtle underwear and watching G.I Joe while sipping on a cold glass of chocolate milk; the ideal morning for a young boy. At the end of each episode was a lesson for the young audience, something about safety (look both ways when you cross the road), health (eat your vegetables), or some other silly public service announcement. I don’t remember my response to these tidbits; I was more interested in the destruction of COBRA Command, but following each was the phrase, “knowledge is half the battle.”

Fast-forward a few decades to 2014, and that show-concluding line became the basis for a fallacy coined by Ariella S. Kristal and Laurie R. Santos. The fallacy points out that “knowing about one’s biases does not always allow one to overcome those biases.”

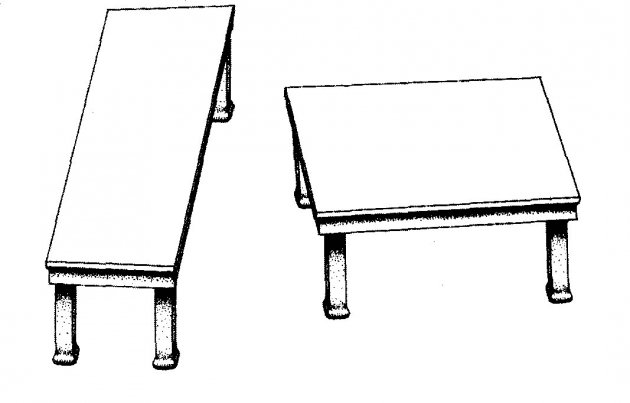

Would you believe that the picture above shows two parallelograms of identical dimensions? Even once we’re made aware that the shapes are identical, it’s hard to believe. The creator, Stanford Psychologist Roger Shepard, said, “any knowledge or understanding of the illusion we may gain at the intellectual level remains virtually powerless to diminish the magnitude of the illusion.”

Unfortunately, knowing is not half the battle. If that were true, we would all easily defeat the cognitive biases that keep us from having better relationships, achieving our long-term goals, and attaining and maintaining a high level of happiness. Our minds’ strongest intuitions are often wrong.

Hedonic Adaptation Can Be a Happiness Killer

In Kentucky, it feels like more bourbon is collected than consumed. People wait in long lines on their days off work to score the latest release of limited bourbon. If you drive by Buffalo Trace Distillery on a Saturday morning, you’ll likely see a score of bourbon fanatics chomping at the bit to get into the gift shop to buy a bottle of revered bourbon. Many of these bottles will sit on shelves, more likely to be the subject of an Instagram post than poured, toasted, and drank. I remember desiring these rare bourbons and even purchasing many of them before the long lengths surpassed my tolerance.

Not long after an excellent score, I would be right back where I was before, desiring the next big release and then the next one. Hedonic adaptation describes the human tendency to return to a base level of happiness after positive (or adverse) events. This phenomenon has been observed in lottery winners and those who’ve survived severe trauma alike. And while this function likely serves essential purposes for human survival, it can make materialistic pursuits unimportant to being happier.

In the class, Santos recommends savoring to battle the hedonistic treadmill. She describes savoring as “the act of stepping outside of an experience to review and appreciate it.” By taking time each day to savor experiences, we can learn to appreciate the good in our lives and live in the moment instead of thinking ahead or reflecting on the past.

Affective Forecasting: We’re as Bad As Meteorologists.

It was about 200,000 years ago when humans first communicated with the spoken word. You’d think that’d be ample time to pass along enough information for us to become accurate forecasters of happiness. Despite personal experience and lessons from others, we’re still largely incompetent in predicting what will make us happy and to what degree. We’re equally bad at predicting the impact of adverse events, often expecting they will be far worse than reality. Our poor forecasting doesn’t end there. We’re not so great at estimating the length of time our emotions will be affected by particular events. Ultimately, we’re as accurate as the worst weather person when it comes to forecasting our happiness.

The Mind Doesn’t Think in Absolutes.

It’s usually not about how much money you make or how big your house is that is important to you. Instead, it’s about your income compared to your co-workers and your home relative to your neighbors. The human mind uses reference points instead of absolutes. This, of course, can be bad for the psyche and even make positive outcomes feel negative. For example, if you get a raise at work, you might be happy to have some extra income. But if you find out your raise was less than your co-workers, suddenly you aren’t so happy, even though you’re making more money than before.

The Ebbinghaus Illusion demonstrates this idea. The two circles below are the same size; however, the circle on the right appears larger due to outside references.

Reference points don’t just come from the outside. The first point of reference is our current situation. Santos points out that when asked how much one would like to make, the person making $30,000 per year will say $50,000, but someone making $100,000 might say $150,000. As you ask people with higher salaries, the answer grows and grows.

Even worse, our minds don’t use reasonable reference points; instead, they use whatever is available. O’Guinn and Schrum (1997) looked at how time watching television impacted our perceptions of wealth. Unsurprisingly, they found that more time in front of the television led to an increase in estimates of other people’s wealth and a decrease in one’s assessment of their wealth. This function of the mind, which assuredly served evolutionary purposes, is detrimental to modern living.

As I continue working through the course and accompanying exercises, I’ll share more of my favorite insights in subsequent posts.